Societal concerns about the welfare of conventionally housed laying hens has led to the global adoption of cage-free systems. As adoption increases, so too do producers’ concerns around potentially higher mortality.

A comprehensive study published in a Nature journal, however, has found that those concerns are generally untrue. In fact, the research shows that mortality gradually drops with time, as producers gain management experience. The study’s findings could reframe the debate on the welfare of laying hens in cage-free systems.

How the study was conducted

Led by Dr. Cynthia Schuck-Paim, scientific director of the Welfare Footprint Project, the study encompassed data from 16 countries, 6,040 commercial flocks, and 176 million laying hens. Across the study, hens were housed in four different housing systems: conventional cages; furnished or enriched cages; and two types of indoor aviary systems, single-tier and multi-tiered. The researchers did not analyze systems where hens had outdoor access.

Schuck-Paim and her team of researchers conducted a systematic review and then a meta-analysis on mortality under commercial conditions in flocks of no less than 1,000 birds. On average, data was collected from very large-scale flocks.

In order to be included in the study, the year of mortality had to be recorded in the dataset. The data also had to be dis-aggregated by housing system, meaning it had to be clear which dataset belonged to which type of housing system. Data the researchers included spanned from 2000 to 2020 and was reported in English, French, Portuguese and Spanish. Several countries provided multi-year datasets of their own, including the Netherlands, France and Norway. Having access to multi-year datasets from a single country was especially advantageous, Schuck-Paim says.

“We could analyze within a single country, how mortality changed over the years for that country,” she says.

The study was comprehensive in that the researchers screened nearly 4,000 data sources. Of the 6,040 flocks they evaluated, 4,407 were caged (3,066 in conventional and 1,341 in furnished cages) and 1,633 were in indoor, cage-free systems (412 in multi-tier aviaries, 290 in single-tier aviaries and 931 flocks where the type of aviary was not defined).

The results

What the data showed was that in the newly adopted systems – enriched cages and aviary systems included – cumulative mortality dropped over time.

“Actually, the best cage-free systems have lower mortality than the best conventionally-caged systems,” Schuck-Paim says. “Producers moving in that direction, can be hopeful that that this will be the case for them, unless they have very poor management, stockmanship and so on.”

In conventionally housed systems, however, mortality has not decreased over time since the year 2000. Instead, it has already reached a plateau, Schuck-Paim says.

In analyzing the most recent data sets, Schuck-Paim says they found no significant difference in mortality between the caged and cage-free housing systems. In fact, commercial Hy-Line data shows that the best cage-free systems have lower mortality than the best caged systems. With that said, there is higher variability in mortality in cage-free systems. To avoid this, producers need to pay more attention to management.

“And that’s why you’ll see that as you get experience over the years, mortality goes down,” she says. “Because you do need to adopt best practices and to know how to manage these other systems.”

Overall, though, mortality gradually drops as experience builds with each system. Since 2000, each year of experience with cage-free aviaries was associated with a 0.35 to 0.65 per cent average drop in cumulative mortality. Faster rates of decline may be experienced as knowledge is gained and passed on, and as genetics are optimized for better health and welfare, Schuck-Paim says.

Beyond the basic analysis of mortality, the researchers also analyzed the data controlling for variables, including flock size, whether they were white hens or brown hens, and beak trimming status to see the effect of these variables on mortality. Overall, 84 per cent of flocks included in the study were of beak-trimmed hens. Approximately half of the intact beak flocks were located in Norway, where beak trimming was banned in 1974. Under this analysis, the results were the same. That is, mortality lessens over time as management improves.

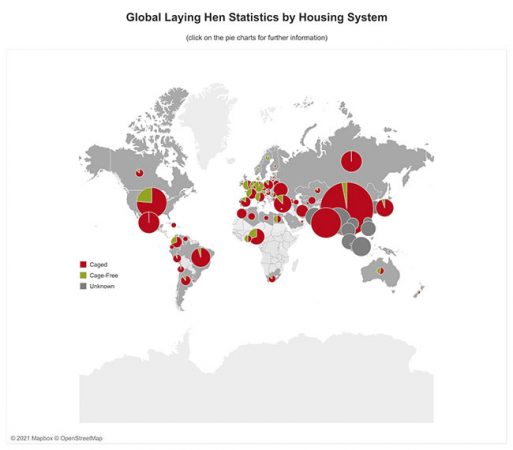

Global laying hen statistics by housing system.

“If you have that experience and know what works and what doesn’t, then mortality can be very low,” she adds.

Schuck-Paim was unable to expand on which management practices helped to lower mortality in this specific study, as her team did not investigate this further. But she did point to a couple of European projects that have done so: FeatherWel and Hennovation.

Funded by the EU, the Hennovation project explored two areas of concern – injurious feather pecking and end-of-lay during transport and at the abattoir. Recommendations related to injurious pecking include: the management and control of poultry red mites; the development of practical lists to advise farmers as to how to prevent further development of feather pecking after first signs of the problem occur; and the effects of lighting, including colour, intensity, daylight and scheduling.

Recommendations related to the welfare of end-of-lay hens include: knowledge transfer on best practices and guidelines; and optimal ways of catching birds in non-cage systems.

The aim of the FeatherWel project is to provide advice on practical strategies to reduce the risk of injurious pecking that occurs in non-cage laying hens during both the rearing and the laying periods. The project compiles scientific evidence, industry experience and the results of the Bristol Pecking Project.

It led to the development of key management strategies, which can be found on the FeatherWel website at featherwel.org.

Schuck-Paim notes that producers can minimize mortality and welfare issues by adopting best practices. For example, when young flocks are introduced to tiered, cage-free systems earlier, they learn how to safely navigate the system at an early age. She notes that delaying the point of lay to over 20 weeks helps to reduce injurious pecking, as well.

In another review of the literature Schuck-Paim conducted, she noted that egg peritonitis syndrome, the leaking of egg material in the peritoneal cavity, is one of the biggest drivers of hen mortality. Reducing in the incidence of egg peritonitis will reduce the overall risk of mortality, Schuck-Paim says.

A cleaner environment will also reduce the risk of infection. Proper diet, homogeneous lighting, and access to litter from day-one are all crucial to proper development and minimizing health and welfare issues, she says.

Although Schuck-Paim’s study did not include cage-free systems with outdoor access, the Hy-Line data did.

Their data did not show higher mortality in cage-free systems, even in those with outdoor access. This was surprising, as many in the industry have expressed great concern about increased mortality due to predation and pathogens.

“Our results speak against the notion that mortality is inherently higher in cage-free production and illustrate the importance of considering the degree of maturity of production systems in any investigations of farm animal health, behaviour and welfare,” she concludes.